An Expert in Emergencies

An Expert in Emergencies

Communication Studies professor shows how communication is key to better disaster response

Communication Studies Professor Keri Stephens has spent a lot of time in rural communities throughout Texas this year: touring storm-ravaged towns, meeting with county emergency officials, surveying properties where residents have been forced to gather dirt, hay and old tires — anything they can find — to build barriers around their homes to keep them from flooding.

It’s these small Texas towns that are getting hit hardest year after year by disasters — hurricanes, wildfires, floods and drought. They don’t have the money needed to build better infrastructure, regulations to prevent people from developing in flood-prone areas or the data required for grant applications to get emergency funding from the federal government. So, several state groups are starting to fund research to send experts to these rural communities to understand how they can help.

But what does any of this have to do with communication?

According to Stephens, it underpins everything about how we prepare for, talk about, stave off and recover from disasters. It’s not just scientists and engineers who are needed to come up with solutions to the next potential catastrophe. It’s communicators, too.

“Our expertise is to come in and figure out what these communities need,” Stephens said. “Whether it’s educational materials, tools to help officials communicate risk to residents or data sets they can put in grant proposals to get needed funding.”

Stephens is an expert in disaster communication, which isn’t really a field of study but one that has sort of grown up around her as she’s explored the different facets of communication involved in emergency response over the past five years. Her early work was in crisis communication, helping businesses prepare and respond to unexpected events. Then Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017 and paralyzed the entire state. Stephens decided to shift her focus. Disaster communication really needs an understanding of crisis and risk communication, she said.

In the years since, Stephens, along with other Moody College faculty from communication studies; advertising and public relations; and journalism and media, has led and been involved with dozens of projects to help improve disaster preparation, response and recovery in Texas, something that has become increasingly important because of changing weather conditions and rapid growth and development that has increased urban flooding.

“We’ve put a lot of effort toward technical solutions, making sure that we have floodplain maps, understanding who can build in a floodplain area or not,” Stephens said. “But the big gap that people are realizing now, we don’t talk about this in a way that people can understand it.”

This past year, Stephens won a UT Tower Award for Outstanding Service Project for her work on the Comanche Trail Community Wildfire Drill, a first-of-its-kind community-wide fire drill that she helped organize in the Steiner Ranch neighborhood in northwest Travis County. On a Saturday morning in March 2019, more than 200 residents responded to a mock emergency alert of a wildfire. They gathered their pets and personal belongings, got in their cars and made their way down a narrow road to an evacuation rendezvous point along Lake Travis.

Imagine the fire drill you did at your elementary school as a kid times 1,000.

The experiment taught Stephens a number of things, most notably, how important community is in disaster response.

“The more you feel like your friends and neighbors have an expectation that you will be prepared, the more likely you are to get prepared,” Stephens said. “This is important because a lot of preparedness literature focuses on individuals and why you need to have an individual plan. We are a very individualistic country. But we need to start talking about preparedness in a group context. I think this is a classic example of how communication can have a direct impact on saving people’s lives.”

But Stephens’ work isn’t just focused on human solutions. In her research, she has also explored the possibility of using artificial intelligence to improve disaster response.

At the start of the pandemic, Stephens began working with emergency departments in Maryland, helping volunteers train computers to identify important disaster communication on social media. People post a lot of critical information on Facebook and Twitter during emergencies — whether their roads or homes are flooded or if they don’t have power or food. Yet, it’s impossible for a single person to scan thousands, if not millions of posts, to find information that could be helpful to emergency responders. Humans, though, can teach computers to find this information on their own through machine learning, helping them recognize important words and filter out the “noise” that isn’t useful. It’s what is known as “human in the loop,” humans working in tandem with AI. And it’s becoming especially important in disaster response as younger people opt to communicate on social media, rather than calling 911.

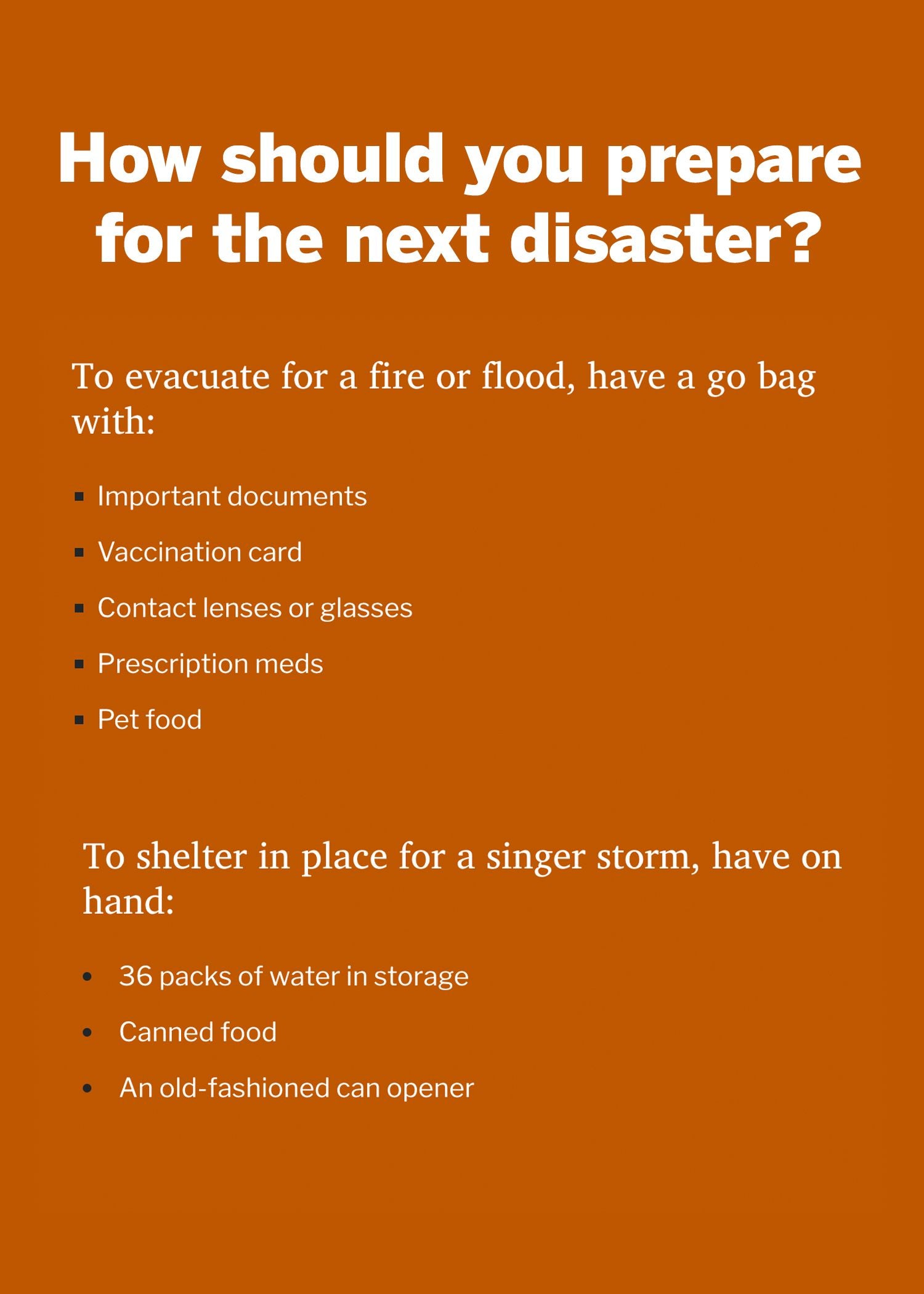

But even with the best data and communication skills, disasters will happen, which is why Stephens said it’s always important for individuals to be prepared. Have a “go bag” ready with the essentials if you can’t return home for a week. Also, make sure you have bottled water, canned food and other necessities if you’re forced to shelter in place. It sounds simple, but Stephens said she’s been surprised how many people are unprepared.

“People are moving to different cities, states and countries, and they have different education and experience about disasters based on where they have lived,” she said. “Also, a lot of the language used by emergency management is jargon that the average person doesn’t understand and is embarrassed to ask about. I think that’s where communication scholars can help. We have a lot of different people at Moody College that can bring their expertise to this problem, including advertising experts, linguistic experts, people who understand organizing behaviors and journalists who can reach audiences. We think carefully about the words being used and who we’re trying to reach. It’s not something that people outside of communication live and breathe like we do. This is why I think the communication fields are in such a great position to help.”