The Post

In 1971, a military analyst disillusioned with the Vietnam War leaked to The New York Times an internal report known as the Pentagon Papers. Commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in 1967, the documents detailed the history of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia leading up to and during the conflict, and revealed harsh truths that multiple administrations hid from the American public.

The Times published its first story on June 13, 1971. Within days, the Nixon administration went to court and a judge granted an injunction that temporarily halted publication.

Meanwhile, The Washington Post obtained a copy of the Pentagon Papers and began publishing, and the legal fight escalated to the Supreme Court. On June 30, 1971, by a vote of 6 to 3, the Supreme Court sided with the newspapers, ruling that the government had failed to meet its “heavy burden” of justifying prior restraint against the press in light of First Amendment freedoms.

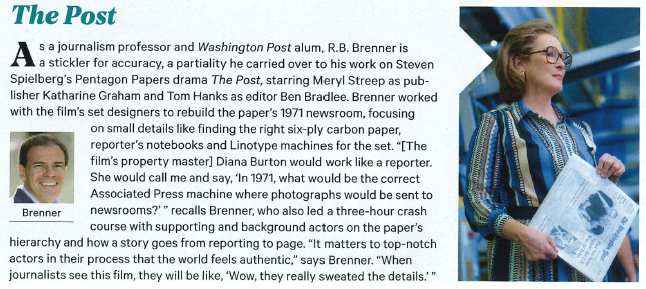

The struggle to publish the Pentagon Papers is the subject of “The Post,” Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-nominated film starring Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep. In order to faithfully portray The Washington Post’s newsroom and journalists, filmmakers enlisted School of Journalism Director R.B. Brenner—himself a veteran Post editor —as one of its consultants.

Brenner joined us to discuss his role consulting on the film and the effect of big screen portrayals of journalists.

How did the partnership come about?

I was contacted last March by one of the film’s art directors and the property master. They were on a tight deadline to design and decorate the sets. They heard about me because I had been a consultant on a newspaper-themed film, “State of Play,” which came out in 2009. When we spoke on the phone, they didn’t need to say anything more than “Spielberg” and “Pentagon Papers,” and I was in.

What were your contributions to “The Post”?

My primary contributions were during pre-production. One of the big challenges was to help re-create what The Washington Post newsroom looked like in 1971. I had to be frank with them: I was 10 years old at the time of the Pentagon Papers, and a lot changed in newsroom culture and certainly with technology between then and the early 1980s, when my professional reporting career began. So, I approached the movie research much like a reporter would dig into a story. I found sources – former Post colleagues who worked there in 1971 – and interviewed them at length, trying to draw out their recollections in as much cinematic detail as possible. Then I searched for old photographs and archival documents. I was fortunate because the Ransom Center is the home of legendary Post Editor Ben Bradlee’s papers. I spent a lot of time looking through that material.

As the production moved toward the start of filming in May, I had in-depth conversations with the directing team right under Steven Spielberg. We discussed the various roles in a newsroom, how a reporter would work differently than an editor, for example. The filmmakers also wanted to better understand the pace of a day, when would the newsroom be crowded and intense and when would it be slower? In 1971, the rhythm of a morning newspaper was synced to printing press deadlines. There’s a big difference in the intensity of activity at 7 or 8 p.m. compared with 10 a.m.

What were the most interesting things you witnessed on set?

I was fascinated by how Spielberg approached the filming of scenes with a clear game plan, a vision he had in mind, yet he was very open to spontaneity and creative ideas from others. At the outset, he would lead a walkthrough of a scene for camera positioning and blocking and to prepare the actors from a performance standpoint. There were three Washington Post consultants: me, former managing editor Steve Coll and Leonard Downie Jr., who was Bradlee’s managing editor and successor as executive editor. We rotated in shifts. As a consultant, I would stand close enough to watch and listen and be available to answer questions. On occasion, I would offer a suggestion. To give you an example, there’s a scene where Post journalists gather around a TV set to watch Walter Cronkite report the news of a judge’s decision that stopped The New York Times from further publication of the Pentagon Papers. The original dialogue was a bit generic. Steve Coll and I, as consultants on the day, mentioned that a breaking story was unfolding. Spielberg immediately picked up on that, and they came up with a new line of dialogue in which Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks, assigns the story to a reporter and says, “That’s tomorrow’s front page lead.”

R.B. Brenner's role as an advisor on "The Post" was profiled in The Hollywood Reporter.

"The film explores the vital role that journalism plays in a democracy."

How was it working with Spielberg and his team? Were they easy to work with and open to collaboration?

The film explores the vital role that journalism plays in a democracy. Everyone involved in the production showed a great deal of respect for journalists and what we do. This helped me feel more at home, though I was never completely relaxed around Spielberg, Hanks and Meryl Streep. The filmmakers were also upfront with us that their job is to entertain people. One scene, for instance, is especially fanciful — Bradlee sends an intern scurrying to New York to sleuth out if The Times was about to publish an investigative blockbuster. I’ve never seen a reconnaissance mission like that in real life, but it was kind of amusing on screen.

Was there anything that surprised you about his approach to the subject matter or as a director in general?

What struck me was the level of trust among Spielberg and his creative team. Most of them are longtime collaborators, including cinematographer Janusz Kaminski and first assistant director Adam Somner. There’s a lot of shorthand in how they communicate. The film is dialogue-heavy, but well written, and Spielberg imbues what could be static material with tension and even frenetic action at times, particularly in the final hour. It’s a magic trick.

Why did the crew and cast feel this story was important to be told?

Liz Hannah, who wrote the script and later collaborated with screenwriter Josh Singer, was inspired by the late Washington Post Publisher Katharine Graham’s autobiography. Mrs. Graham is one of the most important women in American history, certainly in media history, and in November 2016 our country appeared ready to elect a woman President of the United States. But by the time the film’s production got fast tracked, Donald Trump was in the White House — and we witnessed a U.S. president labeling reporters “the enemy of the people.” The film uses actual recordings of Richard Nixon venting against The New York Times and The Washington Post, and of course Nixon’s attempt to stop the newspapers from publishing the Pentagon Papers resulted in a historic Supreme Court case concerning freedom of the press. Words that Nixon is heard uttering on those tapes are eerily similar to what we’re hearing now, except now they’re tweeted.

What can young journalists—who work in an industry very different from that in “The Post”—take away from the film?

Woodward and Bernstein inspired many young journalists of my generation. Their Watergate reporting, and the film portrayal in “All the President’s Men,” led me to regard journalism as a calling much more than a job. You’re providing people with information they need to be informed citizens and trying to keep the powerful from abusing power. I believe this film, “The Post,” will have a similar impact on a new generation of young journalists. Watching the movie in a theater for the first time, I wiped tears from my eyes when part of the Supreme Court’s majority opinion was read aloud. It stated that the role of the press in our country is to serve the governed, not the governors.

How do you think Hollywood portrayals affect the field of journalism? Are there aspects that are beneficial or problematic?

Films like “Spotlight” and “The Post” are reminders of journalism at its best. What bothers me is when a journalism movie strays too far from plausibility, unless it’s a biting satire like “Network,” one of my favorite films. I’m proud of my consulting work on “State of Play,” and I believe that movie is underrated. But it had a few moments when the fictional reporters did things the real journalists I worked alongside for three decades would never consider doing —such as pay for information or videotape a source without consent.

Is there an aspect of journalism that Hollywood has ignored that you would like to see portrayed on the big screen?

A number of journalists at very small local news outlets are doing heroic work in their communities. I’d like to see the story of the two- or three-reporter newsroom that’s fighting the same fights as The Washington Post, often against longer odds, and serving as the public’s eyes and ears and watchdogs. There’s drama in those newsrooms, too.