'Everyone Can Have a Voice'

'Everyone can have a voice'

Moody College Speech and Hearing Center helps people communicate for 85 years

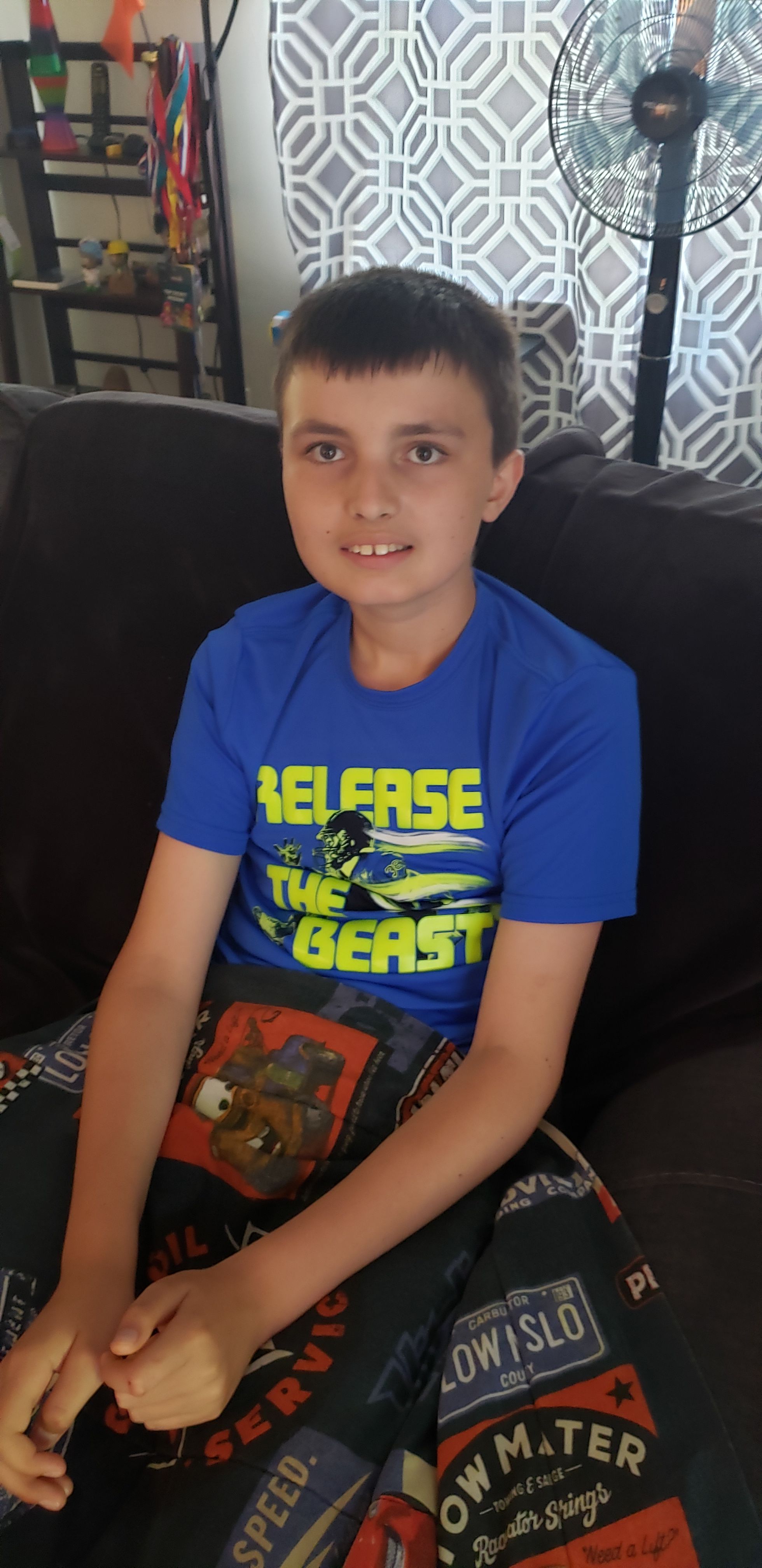

Stefan Adler was by all respects a healthy child. Born a whopping 10 pounds, he spoke his first words at 10 months and went on to learn three languages as a toddler — English, Serbo-Croatian and Italian.

When he was about four, his mom, Natasha, said he started mixing languages, something that is normal for bilingual speakers. But quickly, he began speaking less and less. His parents thought, perhaps, he was being shy. But by the time we was five, he had little to no functional speech. He could say only about five words.

After a battery of tests, doctors diagnosed Stefan with regressive late onset autism spectrum disorder, a rare condition that occurs when a child appears to show typical social, emotional and language development, and then loses their speech and social skills for no discernible reason.

“I remember when he got the diagnosis, my husband and mom cried a lot,” Natasha said. “I didn’t cry because I thought, in a year or two, he’ll bounce back. We are going on 11 years now."

“I remember when he got the diagnosis, my husband and mom cried a lot. I didn’t cry because I thought, in a year or two, he’ll bounce back. We are going on 11 years now."

Today, Stefan is 15 and towers at 6 feet 5 inches tall. He just started his sophomore year at Jackson High School in Hays County. He enjoys playing basketball, though he doesn’t appear to understand the mechanics of the game. His mom describes him as calm, polite and positive.

Through the years, Natasha and her husband have tried everything to help Stefan learn to communicate, from pursuing the best medical solutions to trying out natural remedies. In 2021, a pediatric neurologist at Dell Children’s Medical Center referred Stefan to Moody College of Communication’s Speech and Hearing Center, located on the UT Austin campus, where students gain clinical experience under the supervision of faculty by providing needed services to the Austin community. There, doctoral students Mimi LaValley and Cissy Cheng began looking for ways to help.

“Stefan came to us with a fantastically thorough medical history. His doctors did all the neurological and genetic testing they could do,” LaValley said. “Our job was to look at where to go from there, to see what kind of tools we can provide him to help him communicate."

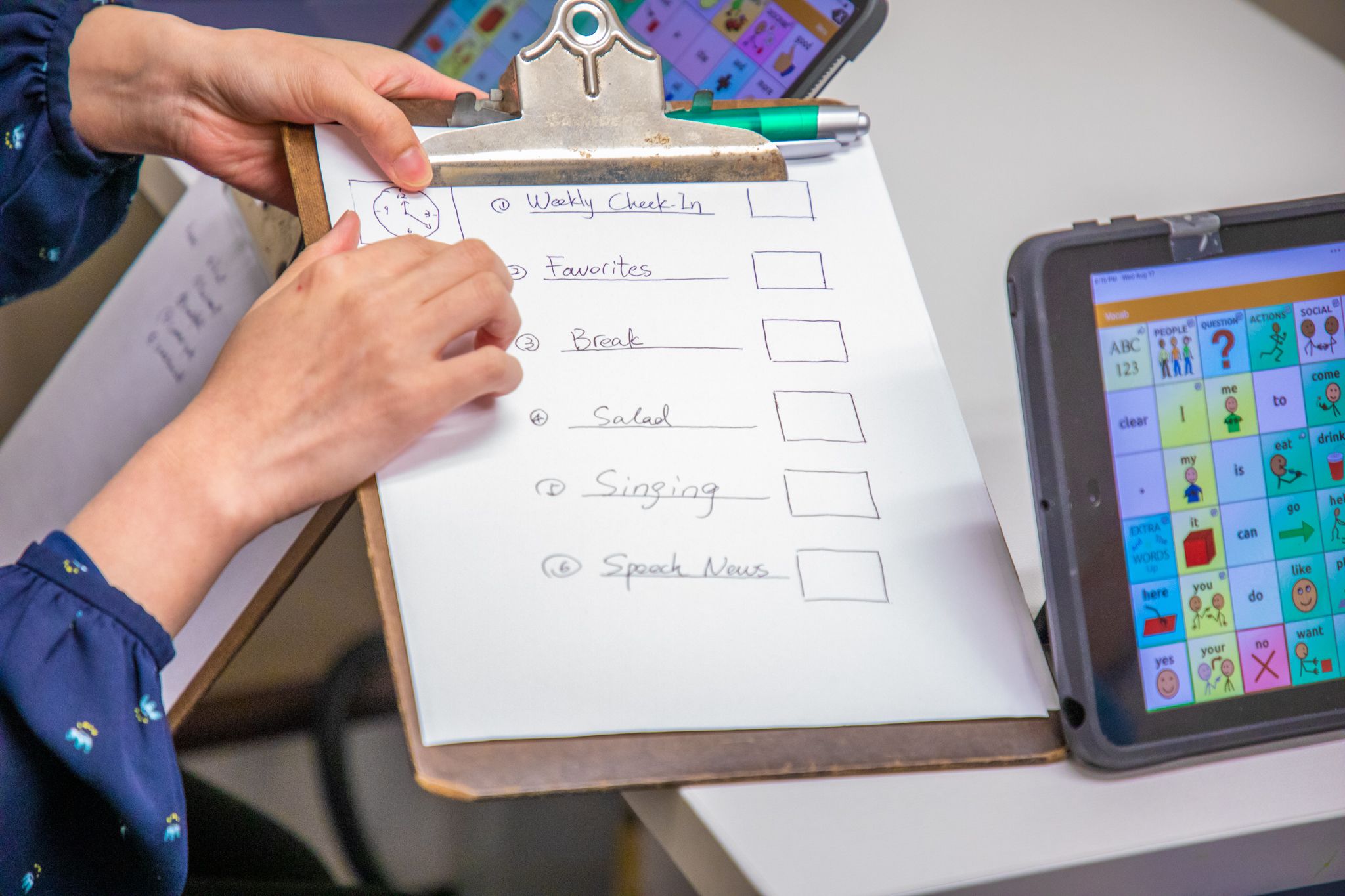

LaValley and Cheng use what is called AAC, or augmentative and alternative communication, to help Stefan convey his thoughts and ideas. AAC is a broad term that refers to everything from signed language to smart devices — anything to supplement or replace natural speech and writing. In Stefan’s case, he uses a tablet with a taxonomy of symbols. He can navigate through different topic areas — from food to sports — to find the subject he wants to talk about. The device also has a keyboard so he can spell out words or select numbers.

“When we are thinking about communication, we always think about language and speech, but there are a lot of ways people communicate,” Cheng said. “AAC is one of those other alternative communication strategies.”

LaValley said it’s important for people who don’t communicate verbally to have access to these tools. Without them, it is very challenging for them to learn, and they are at risk for not understanding literacy, numbers, math and language.

“We don’t do a great job in schools of helping people develop language in alternative ways,” she said.

Twice a week, Stefan comes into the Speech and Hearing Center, and LaValley and Cheng walk him through a number of activities, everything from making a grocery list on his tablet to asking Alexa to play song. They routinely ask him to share news from home and activities he did with his family or around the house. LaValley and Cheng always encourage him to share his opinions, make his own choices and to initiate requests, things that are difficult for people with communication impairment. Stefan typically waits for people to tell him what to do and has trouble expressing his own feelings. If Cheng says her favorite food is ice cream, Stefan says his favorite food is ice cream. However, since starting work with LaValley and Cheng, that’s started to change. He surprised the team in one session by sharing his real favorite food: popcorn.

Natasha has been overjoyed to see Stefan’s progress.

“Mimi and Cissy have a great talent with teenagers like Stefan, and I, along with our whole family, appreciate all that they do,” Natasha said. “Their knowledge, patience, motivation, dedication, poise, tenacity and drive have been key attributes in helping Stefan learn better.”

Both LaValley and Cheng are pursuing their doctoral studies with emphasis on AAC with Raj Koul, chair of the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and director of the ACC Lab. The lab focuses on improving the effectiveness of technology-based AAC interventions for people with severe speech and language impairment as a result of developmental and acquired conditions.

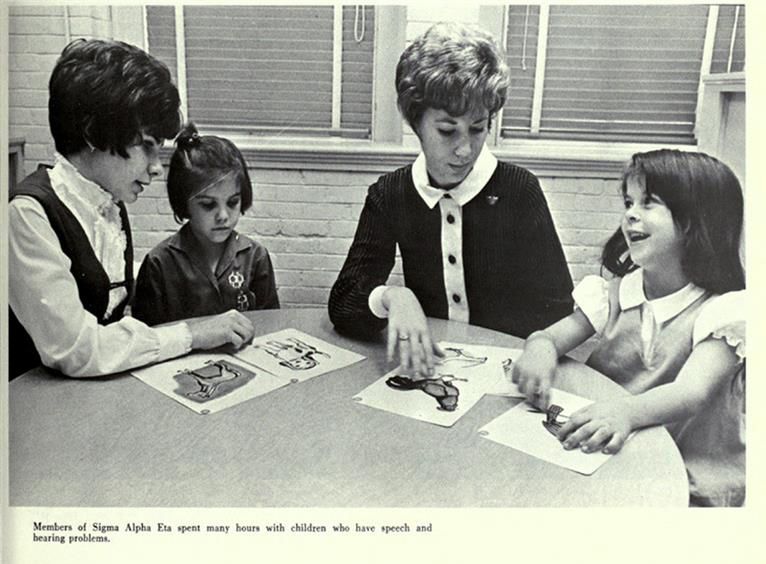

LaValley, who is already certified as a speech-language pathologist and is now earning her doctorate, said working in the Speech and Hearing Center has been an incredible opportunity. Founded in 1937, it was the first speech and hearing clinic in Texas. At that time, it was located on the 25th floor of the UT tower and was a part of the Department of Public Speaking. Over the years, it moved to several locations on campus — in army barracks near the engineering building, then the old speech building near the tower, and finally, in 1974, to its current location in the Jesse H. Jones Communication Complex.

The center offers a range of services for both kids and adults, helping with problems related to speech, hearing and language impairment, as well as treating people with autism and other developmental and acquired communication impairments, and providing a broad range of audiological services. It also provides Moody College’s speech, language, and hearing sciences master’s students with an opportunity to gain clinical experience to prepare them for their careers, while at the same time benefitting the community by providing affordable and first-class services to patients. LaValley said, in a lot of ways, it’s better than simply going to see a specialist.

“You are working with the student, the student supervisor and the whole academic brain trust that is looking at their work,” she said. “It is not a lesser experience than just seeing a specialist. It is specialist plus — plus all the energy and passion of a newly minted clinician, who is incredibly inquisitive and curious and is going to work hard on their cases.”

Doctors have never been able to figure out what exactly caused Stefan to lose his speech, and they say it is unlikely he will ever recover it. Cheng and LaValley say the goal, now, is to get him to his “personal maximum,” which means that he is able to engage in as many parts of the various stages of life, from his teenage years to adulthood, as possible. Right now, that’s largely dependent on his ability to initiate communication and to generate language, not just answer questions, which will determine his level of independence.

“Right now, it’s hard to think of his future,” Natasha said. “Will he be fully independent? Probably more likely no than yes. He will probably have some kind of vocational training starting sophomore year. He didn’t regress that much in physical activities, so I think sports will also be an outlet, which is a plus. It would be great to get him to be an extra in movies or a fashion model. He has a lot of things going for him. We, as a family, stay optimistic. I think his future will be very bright since he already has a great and fulfilling life.”

LaValley and Cheng said what they hope people understand is that speech is not the only kind of communication, even though it’s the one our society most values and recognizes. People communicate in all kinds of ways, even without speech production.

“Communication is a basic human right,” Cheng said. “Everyone can have a voice.”