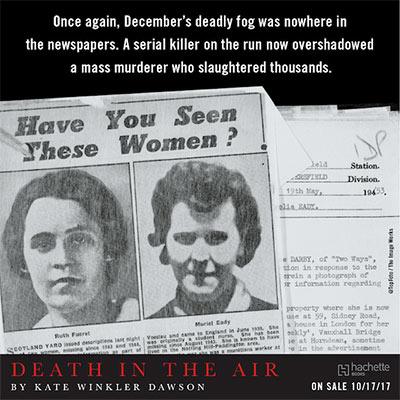

Death in the Air

In 1952, John Reginald Christie roamed the streets of London plotting murder, while a much more dangerous second assassin filled the air. Known as the Great Smog of 1952, the short period between Dec. 5 to Dec. 9 is considered one of the most egregious instances of air pollution in London’s history and to have been directly responsible for as many as 12,000 deaths.

“The Great Smog of 1952 was the world’s deadliest air pollution disaster,” said Kate Dawson, senior lecturer in the School of Journalism and author of “Death in the Air: The True Story of a Serial Killer, the Great London Smog, and the Strangling of a City.” “It was unforgiving and nondiscriminatory. It killed the rich, the poor, members of every religion and race.”

Christie often preferred to incapacitate his victims with coal gas before strangling them, while the air pollution was pervasive and caused irreparable damage or death to the most vulnerable.

In the narrative nonfiction book released Oct. 17, Dawson found further comparisons between the serial killer and the smog mostly arising from the use of coal. Following two years of research during which Dawson conducted interviews in the UK, pored through archival footage, and performed extensive fact-checks, the 339-page book was ready for print.

We interviewed Dawson to learn more about this unique period in London’s cultural history.

What compelled you to write this book? I learned about the Great Smog of 1952 before I learned of Christie and I was shocked that no one had written a book already. It’s such a compelling, frightening story and so relevant today considering the state of our air in this country. Christie’s case was so interesting because he really represented the beginning of the tabloid killer—he attracted so much attention and distracted the public from the real disaster. And there’s a historical landmark with him, too. He was suspected of killing a woman and her little girl who lived above him. The husband was executed for that crime, thanks to Christie’s testimony. It’s considered one of the most well known cases of wrongful execution in the world.

Is Christie still seen as an iconic killer in London or the UK? What about the smog—to what degree has it been remembered or forgotten? Yes, most people in the UK know about John Reginald Christie and his famous address, 10 Rillington Place. There was a well-known movie about it and the BBC aired a short miniseries last year. The Great Smog of 1952 is less known there, absolutely. There’s no monument that exists and it really only appears in the newspapers during an anniversary. And it’s likely that Americans only know about the smog is because it was featured in an episode of the Netflix series, “The Crown.”

How exactly did the smog become overwhelming? Did it lead to future environmental regulations? Pollution was historically a problem in London for hundreds of years, and it killed people every year. The smog in 1952 was more deadly because of a freak weather occurrence, a weather inversion that trapped the pollution over London for five days. There was no wind, so the smoke particles and fumes just stayed there, building and building from millions of coal burning fireplaces.

After growing pressure from Labour politicians—led by one of my characters, Norman Dodds—Churchill’s ministers were finally forced to come up with reforms, but not before thousands of people died. The smog led to the Clean Air Act of 1956, the world’s first air pollution act enacted by a government that uniformly restrained pollution nationwide. It tightened restrictions on industrial smoke and banned coal in many domestic and industrial areas across the country. It was the predecessor to the U.S.’s Clean Air Act of 1970.

You compare the serial killer to the smog as an effective metaphor. How are they similar and different? Well, John Reginald Christie really targeted his victims. He selected women who wouldn’t be missed, mostly prostitutes or women who weren’t close with their families. Even his wife Ethel--his third victim--wasn’t really missed for months. They were a reclusive couple. The fog was nondiscriminatory. It killed anyone it could, really. Any Londoner who stayed around long enough. And of course, the reaction from the media, public and government were starkly different.

They both strangled. They both used pollution to disable their victims. They both used opportunity: the fog struck during the coldest month of the year, when virtually everyone in London, almost 10 million people, were burning coal for warmth. Christie killed women who needed money. Notting Hill, his neighborhood, was a poverty-stricken area and no one was comfortable, yet Christie was always able to offer alcohol, or money, or a warm place to sleep. And then he would assault them and kill them.

Christie murdered at least seven people and likely eight. Estimates vary between how many people were killed by the smog – what number do you believe to be accurate? Well, that’s complicated. The smog absolutely killed as many as 12,000. That’s been proven through analysis of the lungs of victims and medical records. The British government claimed that the smog only killed 4,000 people and that an influenza epidemic killed the rest, but there was no epidemic. And a government official admitted that Churchill’s government fabricated the flu crisis. It was just trying to cover up thousands of deaths.