The Color Complex

Christina Cho stood with her friend outside the Museum of Color on The University of Texas at Austin campus. They have been friends for more than a decade, but after researching colorism for the better part of 2019 at UT Austin and the University of Ghana, Cho said she feared her friend’s reaction to what awaited inside.

Cho’s friend touts blonde hair and blue eyes, the standard of whiteness that many try and fail to achieve. Cho did not know if her friend would take well to messages calling out the ways in which attempts to appear white destroyed the confidence of students at UT Austin.

The pair observed artifacts representing the stories of students’ experiences with colorism, a result of the research done in the year prior. Cho said after reading their stories, her friend related to the feeling of wanting to belong.

“That really brought it down to everyone’s level. To hear the story instead of ‘Here are the terms that are in the textbook,’” Cho said. “‘Here’s colorism,’ ‘Here’s intersectionality.’ ‘Here’s all these buzzwords’ that don’t get to people as fast as ‘Here’s my story.’”

From lightening skin tones to chemically altering the texture of one’s hair, colorism alters the standards of beauty worldwide. It is not limited to one culture, one skin tone or one hair type. For Cho and her friend, the feeling of vulnerability is what made the research resonate. Opening oneself up to the potential of pain is how the Color Complex team started the healing process through their research.

Moody College graduate Rebecca Chen, Timia Bethea, Christina Cho and Vida Nwadiei made up the interdisciplinary group of researchers. The group assembled after winning the President’s Award for Global Learning at UT Austin in early 2019.

The award offered a $25,000 stipend to conduct research in an approved country. All that was required was a team, a region and an idea to set the research into motion. Each coming from different majors within the university, the team wanted to examine colorism outside of the United States.

Though colorism is a part of every community, Bethea said people’s experiences limit their understanding of the concept on a larger scale. Their research sought to analyze the similarities between the effects of colorism at UT Austin and Ghana.

Starting in the spring of 2019, the team conducted qualitative research by interviewing African-American and Asian-American students on campus. That summer, they traveled to Ghana to conduct similar interviews with students from the University of Ghana and citizens from a local town for 10 weeks. The research culminated into an essay, a campaign and a museum in the spring of this year.

During the beginning stages of their research, defining colorism was a challenge. Typically, colorism is seen as disparity among skin types. Lighter skin is strived for because it is ascribed as the colonial standard.

But for Bethea, her research inquiry started by her examining the relationship with her hair.

Bethea said when she began exploring the idea of natural hair, she met backlash from her family members.

For the black community, perms are a common beauty practice, and chemically straightened hair is the professional benchmark. Deviation from this standard can result in a loss of job opportunities and scrutiny from black peers.

When Bethea chose to wear her natural hair, she received a negative response from the community. Black hair, in its natural state, does not align with society's standards of beauty. Bethea did not know her family agreed with that sentiment.

“I never thought that going natural would have made me this deep into the woods on this issue of colorism,” said Bethea, who served as the team’s documentary director. “That was my first time asking myself, 'Why am I told by my own mom, or my own parents and family that they don’t know if my hair would look good natural?’ Who needs to go through that?”

When she made herself vulnerable to her own experience, Bethea said she found her desire to provide a voice to the global issue of colorism.

The data collection stage of research provided a similar awakening for Finance and Media Director Vida Nwadiei. As a Nigerian-American, Nwadiei found the interviews of the Ghanaian students sparked a deeper understanding of her own family narrative.

Ghana is an hour from Nigeria by plane, and the countries share similar social issues.

Ghana’s Food and Drug Administration banned the chemical hydroquinone in August 2016. The chemical, known for lightening the skin, saturated the beauty market in Ghana. The team took that as a sign the community in Ghana acknowledged the effects of colorism.

Much like Ghana, Nigeria has its own problems with the distribution of skin lightening creams and pills. The team initially intended to conduct research in Nigeria. However, due to UT travel restrictions, they focused on Ghana.

For Nwadiei, who graduated with a degree in Kinesiology, she did not know how her major would fit into propelling the narrative forward. But when she started the research, she realized her academic speciality did not matter as much as her personal identity.

Nwadiei said hearing the stories of the students in Ghana sparked emotions she did not even experience back on campus.

“Nigeria is one of the biggest skin bleaching countries in Africa,” Nwadiei said. “After talking to my mom about it, that was definitely something she knew about.”

Nwadiei said her time in Ghana allowed her to reflect on the experiences as a Nigeria-American fighting colorism. She said her motivation stemmed from the need to make a change in her community. Following their initial work on the UT Austin campus and travel to Ghana, the team returned with a new take on how to approach colorism.

At the same time, the healing process began for both the team and the students who participated and lent their stories to the research process.

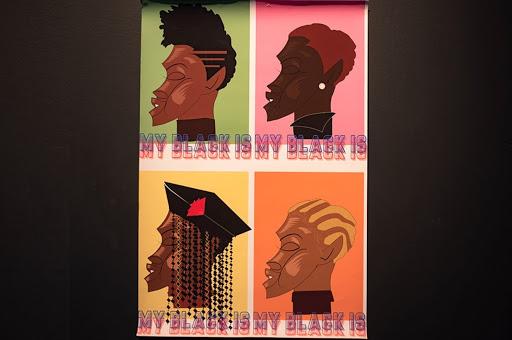

The team spent two and a half months creating the Museum of Color, an interactive art exhibition that highlighted voices of students affected by colorism at UT Austin. The 600 attendees absorbed the pain of their peers, and much like Cho’s friend, reflected on their own experiences.

Chen, the exhibition director, said that spreading awareness of colorism requires self-reflection. Though she recognizes this as a difficult task, the process encourages individuals to explore colorism beyond the borders of the team’s research collective. Chen said checking on yourself to find your true intentions is important when it comes to social research. It is important to maintain honesty throughout the process in order to create meaningful work.

“Why are you doing the things you’re doing,” said Chen, “Are you doing it to uplift yourself, or are you doing it to uplift other voices?”

Chen, a graduate from the Stan Richards School of Advertising and Public Relations, said Moody College students have a unique advantage when it comes to research. Their ability to create diverse and impactful creative works sets them apart from the rest.

Chen said when the students let go of their biases and face their problems head on, they can make statements that impact society.

“We’ve been thinking about colorism in a completely limited fashion,” Bethea said. “By trying to educate people, we also help try and knock down those barriers people put up for themselves.”