Cine de Oro

Among countries that developed distinct filmmaking traditions during the 20th century, Mexico and its “Cine de Oro”—or Golden Age of film—is perhaps the most neglected by audiences and scholars in the United States.

From the mid-1930s to the late 1950s, Mexican cinema became the most successful Spanish-language film industry in the world. During this time, many Mexican filmmakers adopted the dominant Hollywood model for storytelling and production. However, a small faction rejected Hollywood’s model to create a unique Mexican cinematic aesthetic that sought to express “lo mexicano.”

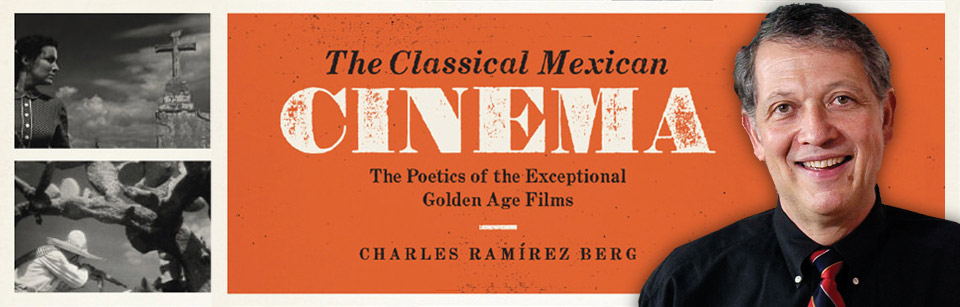

In an attempt to shed light on this important but neglected tradition, Radio-Television-Film Professor Charles Ramírez Berg examines this pivotal period in Mexican film with his fourth book, “The Classical Mexican Cinema.”

The book profiles 50 films, including portraits of seven directors, three screenwriters, two influential artists and one female editor. It was published by The University of Texas Press on Sept. 1. Ramírez Berg sat down with us to discuss his new book.

Why are films from the mid-1930s to the late 1950s considered the Golden Age cinema?

It was a period of great creativity in Mexican cinema, also of the inception and growth of the Mexican film industry into the top Spanish language cinema in the world. Mexico became the Hollywood of Latin America and of Spanish-language cinema for those 20 or so years.

Can you explain what was the dominant Hollywood model of filmmaking at the time and how Mexican cinema differs?

It has to do with the three-act dramatic structure, the happy ending, the studio system, the star system, conventions of shooting, lighting, acting, writing, editing. For the most part, it became the dominant film style in the world. And in Mexico too, it was adopted by most Mexican films. My book is about those films in the minority—but a minority that won awards in festivals around the world—that rejected the Hollywood model and tried instead to create a specific Mexican style to tell Mexican stories for Mexican audiences.

How were the kinds of stories told and ways they were told different in Mexican cinema?

Many were tragedies and not happy ending stories. Many were critical of Mexico, the failure of the revolution from 1910 to 1920 and critical of machismo and Mexican patriarchy.

What do you think readers will find interesting about your book?

Well, one thing for sure is all the illustrations. I knew I needed to have lots of stills included, since most readers would not have seen the films or even be aware of them. So, I captured 250 film stills in order to illustrate my points. In addition, I secured 30 more illustrations from major Mexican artists to show the similarity between Mexican art of the time and Mexican cinema. Also, I have a chapter on the Mexican films of director Luis Buñuel. He is a very well known director, but mainly for the films he made in Europe. Very little is known about the films he made in Mexico and my book fills in that important gap in his filmography.

What films are worth exploring from this era in Mexican filmmaking?

Well, I’d say all the ones in my book. Seriously, the films in the book are the great films in Mexican film history, the festival award winners, and so forth. That is the focus—the exceptional Mexican films from the 1930s to the 1950s and early 1960s.

Where can people find the films you profile?

They are very hard to find. But I’m working on it! Some are on DVDs, but many do not have English subtitles. Several of them can be found on YouTube but many unfortunately, are poor transfers.

Charles Ramírez Berg on new book "The Classical Mexican Cinema" from Moody College of Communication on Vimeo.

A screening of classical Mexican motion picture “Enamorada” is scheduled Sept. 24 at 6 p.m. in the Fine Arts Library (DFA 3.200) with a book signing beginning at 5 p.m. Hosted by Ramírez Berg, a question and answer session will follow the screening and is free and open to the public. Books will be available for purchase along with free beverages. Emilio Fernández directed “Enamorada,” which is about a revolutionary general who falls in love with a fiery and independent woman.

Ramírez Berg has won every major teaching award. He is the author of several books including “Latino Images in Film: Stereotypes, Subversion, and Resistance,” “Cine Mexicano: Posters from the Golden Age, 1936-1956,” and “Cinema of Solitude: A Critical Study of Mexican Film, 1967-1983.”