The bilingual mind

The bilingual mind

Moody College researchers explore how bilingualism impacts the onset and treatment of certain types of dementia

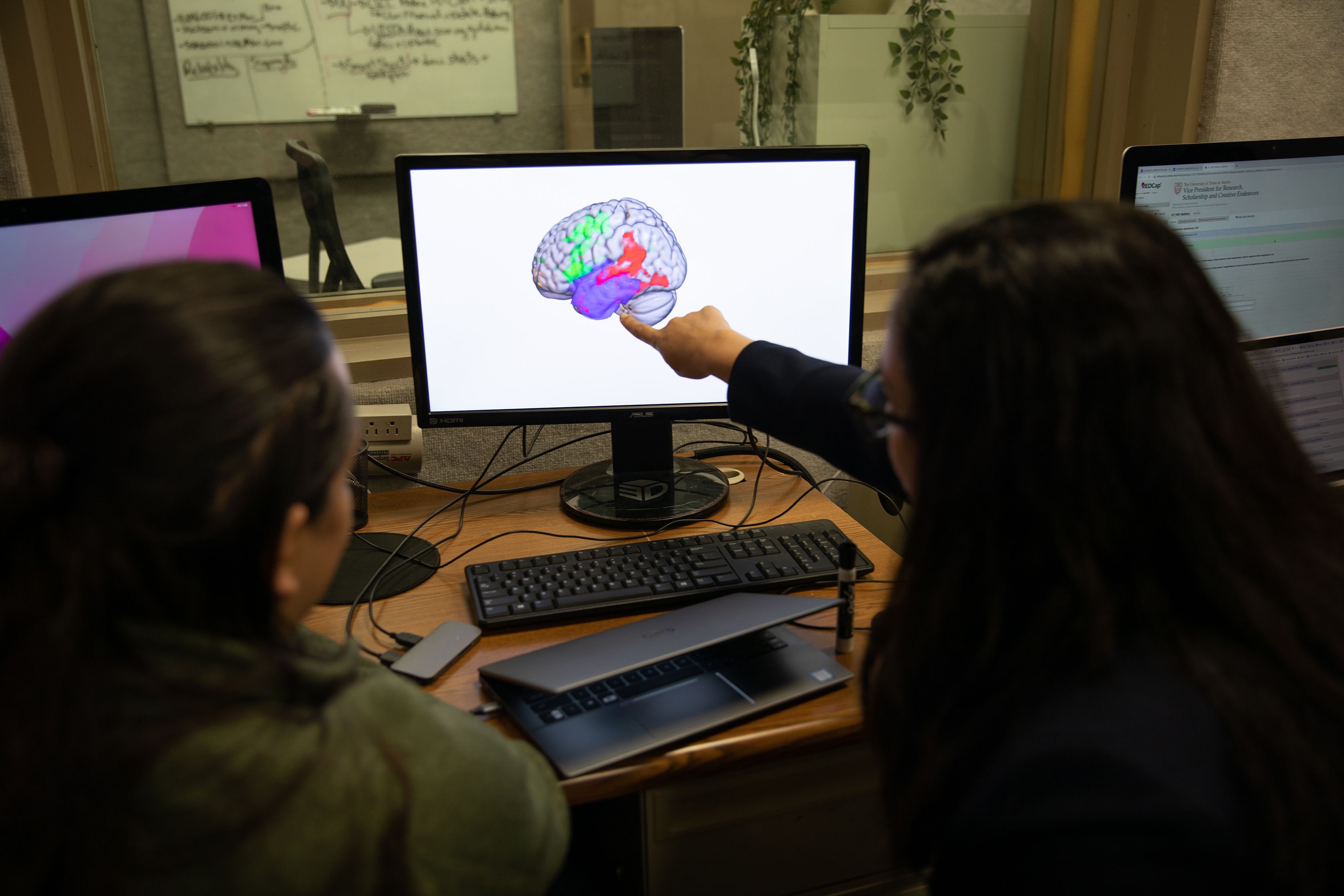

Bilingual people have been found to have a greater amount of tissue in parts of the brain that support communication skills. Scientists suspect this is because of the constant need to control switching between two languages, each of which may have different sets of grammar rules, sounds and vocabularies.

In part because of these physical differences in the brain, University of Texas at Austin researchers are interested in understanding more about how learning a second language could impact the onset and treatment of dementia, specifically speech and language-related conditions such as primary progressive aphasia, which slowly damages the parts of the brain that control speech and language.

New reports find that bilingualism may delay the onset of dementia as much as five years, including some types of progressive aphasia.

“There is nothing that has this kind of effect,” said Stephanie Grasso, an assistant professor in Moody College of Communication’s Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, who is leading the UT research team. “We see that this is present not only in Alzheimer’s dementia but in other types of dementia as well. It’s remarkable.”

“We can look at the ingredients of the bilingual experience and understand what are the critical ingredients that result in the delay in onset.”

With a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Grasso and her team at the Multilingual Aphasia and Dementia Research Lab are working on building a dataset to investigate which factors of the bilingual experience could result in a delay in the onset of dementia symptoms and result in better treatment outcomes. For example, at what age did patients learn their second language? How often do they switch between languages? Does learning a second language at some point in the lifespan prevent or delay the onset of primary progressive aphasia? And how early?

Grasso’s team is conducting its study not only in the U.S. but also in Barcelona, Spain, where nearly the entire population is bilingual. This will help them understand how the bilingual experience might be influenced by the broader sociocultural context or specific languages a person speaks.

“We can look at the ingredients of the bilingual experience and understand what the critical ingredients are that result in the delay in onset, which could help with treatment,” Grasso said. “There are many prophylactic programs that aim to reduce the risk of dementia in healthy people who are aging. Many focus on exercise, diet and things of that nature. We don’t know if we could incorporate some element of second language learning to really try to protect or reduce the risk of the development of dementia. If we know what the critical ingredients are, that will directly impact what that program might look like.”

Miguel Ángel Santos, a neurologist at Hospital de Sant Pau in Barcelona.

Miguel Ángel Santos, a neurologist at Hospital de Sant Pau in Barcelona.

Not only could this information help practitioners treat patients, it could also help governments and public health experts around the world come up with policies and public health campaigns.

“Taking care of patients with dementia is very, very expensive,” said Miguel Ángel Santos, a neurologist at Hospital de Sant Pau in Barcelona, who is working with Grasso and her team on the project. “Obviously the governments of most countries would be very interested in this information. There are lots of policies you can implement that are relatively low cost to promote language learning in school earlier that could result in future benefits.”

Detecting aphasia

Perhaps the first time many people learned of primary progressive aphasia was in 2022 when actor Bruce Willis was diagnosed with the condition. Most people with aphasia lose their language and speech skills as a result of a stroke. In progressive aphasia, this loss is the result of neurodegeneration. Once considered to be a rare disorder, it is now identified more accurately by specialists and can show up in a number of ways.

In semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, people lose their ability to distinguish items — calling a zebra a horse or forgetting the name of an item altogether. In logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia, people have difficulty assembling sounds, making it difficult to form words or sentences. The final type is nonfluent/agrammatic. Patients have a hard time getting their mouth to form what they want to say and may make grammatical mistakes that they didn’t before, such as leaving out small connecting words.

Grasso said it can be hard to catch some of these symptoms early on. For some, it can be mistaken for forgetfulness or even anxiety or depression.

“With a stroke there usually is a clear incident that happened People go to the hospital, get a brain scan. It’s obvious something has changed,” Grasso said. “With primary progressive aphasia it is much more insidious. Individuals and their loved ones may have noticed something was different, but because the symptoms can be subtle at first, and because there is less awareness of primary progressive aphasia, it’s often a long road to diagnosis.”

Many people with primary progressive aphasia die within three to 10 years of onset, largely because of other complications such as pneumonia. However, their quality of life diminishes severely in their last years of life. Treatment options are also limited, as many speech-pathologists feel ill-equipped to treat the condition.

UT Austin’s Multilingual Aphasia and Dementia Research Lab has become an important place for patients who need treatment and haven’t been able to receive it otherwise, offering help through clinical trials.

“These people aren’t seen by speech pathologists in the community very often. They fall through the cracks,” said Maya Henry, the interim associate dean for research at Moody College of Communication and co-director of the lab. “People with an unusual or rare diagnosis have such a tall, uphill battle to get a diagnosis. Not everyone is Bruce Willis.”

“People with an unusual or rare diagnosis have such a tall, uphill battle to get a diagnosis. Not everyone is Bruce Willis.”

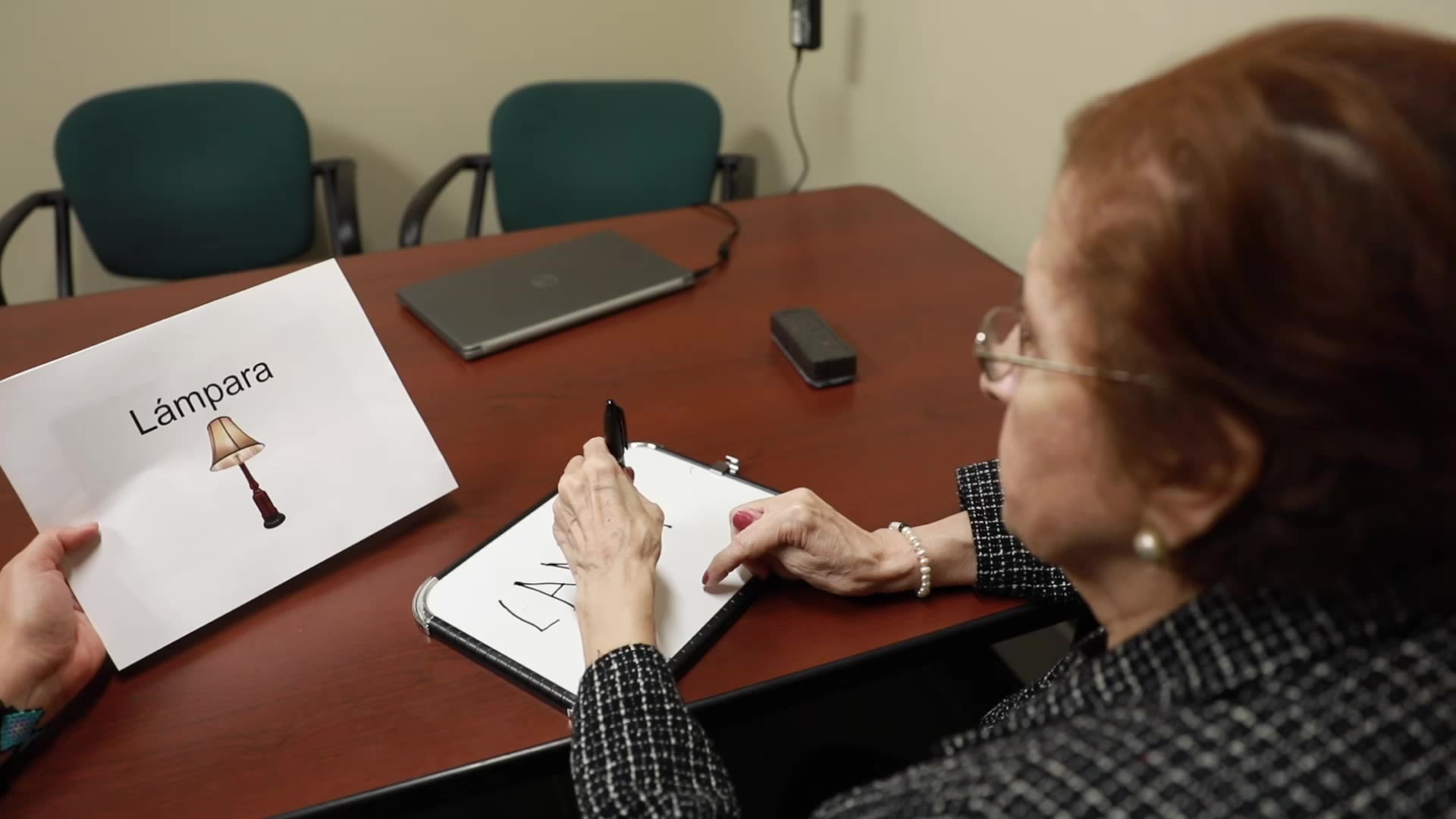

Grasso said treatment is tailored to the communication needs of each person and that approaches usually include practicing strategies to aid in finding words that are hard to retrieve, repeating words and phrases that the person will use in their own day-to-day life and providing patients with a toolkit of different approaches to communication, such as gesture, writing and using communication books. These strategies and approaches are important throughout the progression of the disorder.

“After a six-year speech-language therapy trial, we are seeing that most patients do get better and many have lasting benefits, even up to a year after treatment ends,” Henry said of the clinical trials ongoing at UT. “We aren’t curing the disease, but we are giving them tools to communicate.”

Patients have said before treatment they were afraid to go out with friends or get on phone calls because of their communication challenges. After receiving treatment at the research lab, they are more confident, don’t get as frustrated or nervous, trust themselves more and find they are able to participate in life again.

Expanding understanding

"Ultimately we hope this gives families and individuals with progressive aphasia hope so they can keep communicating and maintain relationships in their lives."

Up until this point, most of the research into primary progressive aphasia has been limited to people who only speak one language. Grasso and her team are hopeful to be able to contribute new knowledge about the disease presentation, progression and treatment in bilingual patients and also provide tailored treatment to these patients, which isn’t available today.

“When I started working in this area as a Ph.D. student, the majority of research available had really been conducted in white, monolingual populations,” Grasso said. “My own background growing up in a bilingual household really made me question what we could do for individuals who speak more than one language. There wasn’t any evidence about treatment options for bilingual or Spanish speakers with progressive aphasia.”

With a $3.4 million grant awarded in 2022 from the National Institutes of Health, Grasso and her team have begun treating bilingual patients who speak both Spanish and Catalan because of the unique sociocultural context and similarity in these languages. It’s possible these people will have particular treatment outcomes because they are able to retain more words by using the similarities between their two languages, or that treatment in one language might benefit the other.

“If they have problems finding a word in one language, maybe they can find the word in another language and use it in their communication. It’s an opportunity if you can choose and use that as a strategy when you are stuck,” said Núria Montagut Colomer, a bilingual speech therapist in Barcelona who has partnered with the UT team to help develop a treatment protocol specifically for these bilingual patients. “Also, if you treat a patient in Spanish, perhaps they can transfer that to Catalan and vice versa. Because bilinguals speak two languages, they may be able to benefit in unique ways.”

"The goal of speech therapy for monolingual and bilingual speakers alike is to increase functional communication, not just for the day-to-day transactions but also for them to continue connecting with their family, their community and live as normal a life as possible as their dementia progresses."

The UT and Barcelona team have selected a large cohort of patients who speak both Spanish and Catalan to receive three months of intensive language treatment — with some sessions in Spanish and others in Catalan. They are administering a number of therapies to help them learn specific strategies for finding words and engage in intensive practice with phrases that are important to each participant, with the intention that they will be able to use their strategies and phrases outside of therapy, in everyday communication. With the practice of phrases, it’s similar to recalling a song that you may have learned as a child. The words and the motor pattern are still there, years later into adulthood.

“That’s sort of the effect we are looking for, an automized pattern,” said Camille Wagner Rodriguez, a bilingual speech-language pathologist who is implementing the treatment protocol at UT. “The more you practice, the easier it becomes to use it when you need it.”

The team’s hypothesis is that bilingual participants will show significant improvements in both of their languages and will show better generalization on words that are cognates, which are words that are similar in both languages, such as dentist and dentista. Wagner Rodriguez said this knowledge will help better treat these patients using an approach that is individual to them, rather than one that’s been developed for monolingual populations with different needs.

“We need to consider the unique needs of bilingual speakers who may have specific contexts in which they more heavily utilize each of their languages,” Wagner Rodriguez said. “The goal of speech therapy for monolingual and bilingual speakers alike is to increase functional communication, not just for the day-to-day transactions but also for them to continue connecting with their family, their community and live as normal a life as possible as their dementia progresses.”

Grasso’s team is also working with the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery in Mexico City, which doesn’t have speech-language pathologists equipped to treat its aphasia patients. Until now, they have only been able to offer medication and family support. Grasso’s team has been able to invite the hospital’s bilingual and Spanish-speaking patients into the UT study. By doing so, the medical professionals at the hospital are also able to learn new treatment approaches previously unavailable to them. It’s a win-win situation, said Erika Mariana Longoria Ibarrola, a psychiatrist at the hospital.

“Sometimes we feel frustrated because we have nothing else to offer patients but medication,” she said. “We are really happy and excited to have this collaboration. We feel like we are learning a lot.”

Stephanie Grasso and her team, stand with their first patient, Norma.

Stephanie Grasso and her team, stand with their first patient, Norma.

One of the things Grasso most enjoys about this work is being able to help populations that don’t have access to the care they need.

“We are interested in developing treatment options in groups that have been historically underserved,” she said. “Communication is a basic human right, and ultimately we hope this gives families and individuals with progressive aphasia hope so they can keep communicating and maintain relationships in their lives.”