'A force that's building and building and will soon explode and change the world'

‘A force that’s building and building and will soon explode and change the world’

KUT’s Nathan Bernier adopts AI in the newsroom

When ChatGPT went mainstream last year, many writers feared they might soon be replaced by large language models that could do their jobs quickly, cheaply and perhaps more efficiently.

KUT’s Nathan Bernier, who covers transportation, admits he was in that camp at first.

But after playing with ChatGPT for a bit, he said he found its writing “atrocious.”

“It is cliched. It takes longer to say the same thing. It doesn’t always know the most conversational words to use,” he said on a Zoom call.

That could change one day, he said, but for now, such large language models just can’t synthesize the information needed to write a compelling, informative piece the way a journalist can — corralling information they read five years ago in a report, something they heard once on the radio, their experience living in Austin all their life, the emotion and vulnerability they get sitting down with a source. These types of AI also don’t have very good news judgment.

Even knowing these shortcomings, Bernier is excited about AI, so much so that when he talks about it, he puts his hands wildly in the air as he calls it “a force that’s building and building and will soon explode and change the world.”

“I have this amazement and disconcerting worry about the future that if I don’t take advantage of this and learn it to its fullest, I will be left behind,” he said.

“Imagine it’s 1995, and you decide you won’t use the internet. You just look through phone books instead,” he said. “This is going to completely revolutionize the world, and I don’t want in 20 years to still be looking through phone books.”

(He knows no one still looks at phone books.)

Bernier is what you might call an early adopter of AI technology in the newsroom and is discovering firsthand the ways it might positively impact journalism.

Today, he uses it to search through his own documents, translate city memos and even help craft important questions before an interview.

As a traffic reporter, Bernier has a lot of PDFs on his computer — documents from the Texas Department of Public Safety, the City of Austin, the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, public information requests. They’re in different folders, organized by agencies. Tens of gigabytes and thousands and thousands of pages. Too much for any one human to efficiently search through.

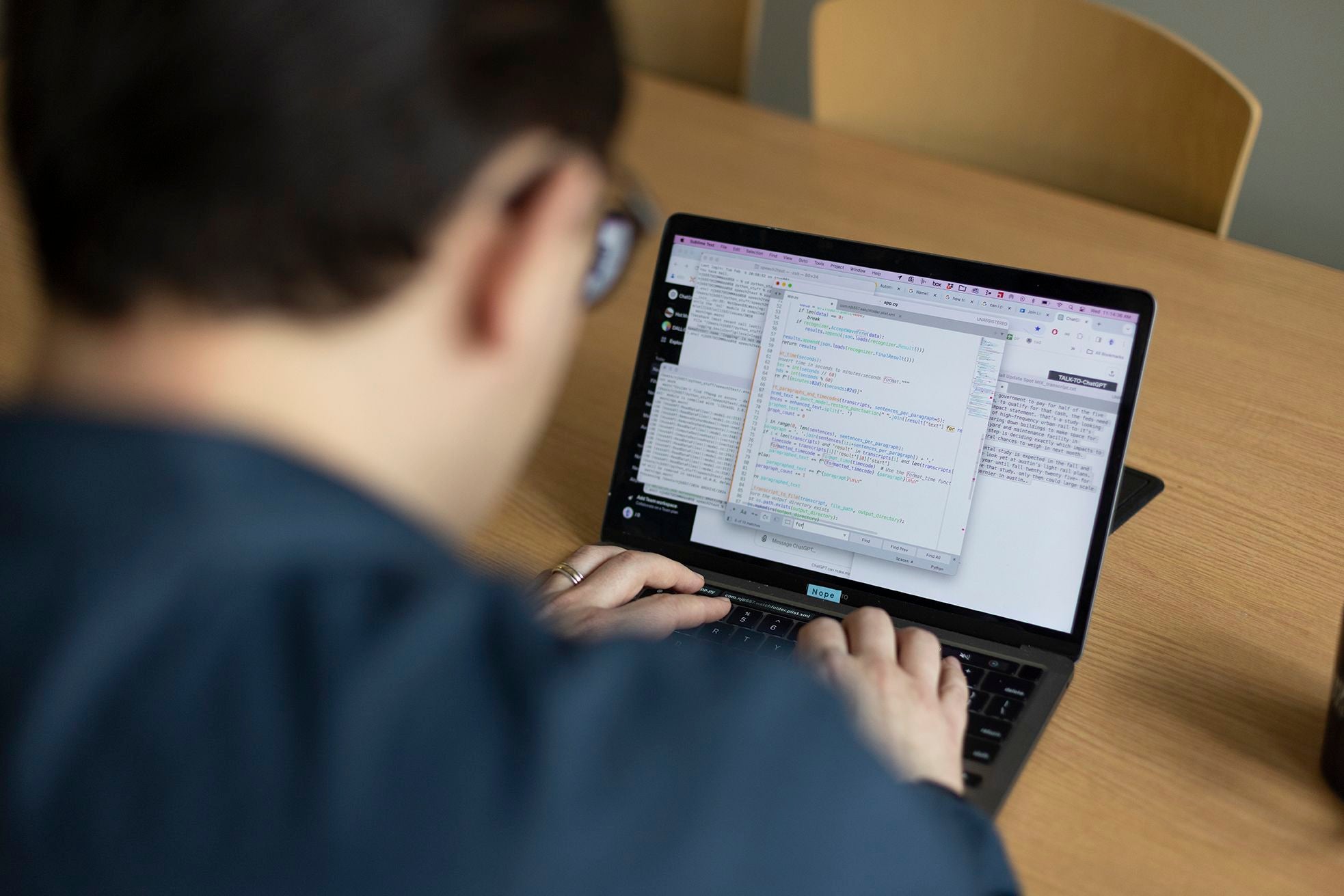

Right now, Bernier is using ChatGPT to help him write a Python code to scan these documents, which makes it easier for him to find information that could help for a story.

“I am drinking from a firehouse on my beat. There’s so much information coming at me and so many stories I can’t keep up,” Bernier said. “ChatGPT is a tool to help me process a lot of information quicker to get closer to the truth.”

"I have this amazement and disconcerting worry about the future that if I don’t take advantage of this and learn it to its fullest, I will be left behind."

Bernier learned coding several years ago, but it takes him a ton of time to write scripts, and he admits he’s no pro. ChatGPT makes up the difference. He can tell it what he needs and ask for help to create it.

Bernier’s work with the AI system also is helping other reporters in the KUT newsroom to uncover important information in city memos.

The City of Austin posts memos to its website daily. They are dry, bureaucratic documents — city resolutions, notes from City Council meetings, updates from Austin Energy, extreme weather plans — that would take loads of time to dig through. He’s been able to use OpenAI API to help write code that can scan these documents, extract text, translate it in plain language and send it to a Slack channel so his team can more easily identify interesting stories and important information.

While these uses have proven extremely beneficial, Bernier still approaches AI with caution. He doesn’t believe it’s at all trustworthy. Its data analysis can be completely incorrect, and everything it spits out needs to be verified again and again.

“I don’t want people to think it is writing my stories for me, because it’s not,” he said. “I would be nervous to put out anything that’s not checked by a human.”

UT General Manager Debbie Hiott has thrown her support behind Bernier but echoes these sentiments. Photo by Gabriel C. Perez/KUT News

UT General Manager Debbie Hiott has thrown her support behind Bernier but echoes these sentiments. Photo by Gabriel C. Perez/KUT News

KUT General Manager Debbie Hiott has thrown her support behind Bernier but echoes these sentiments.

“With any new technology, any innovation, it is our inherent knee-jerk reaction to say that we are doing things fine the way we are doing them,” she said. “I really applaud Nathan and other reporters who want to explore a little bit in a way that makes sense for our organization, doing work behind the scenes that helps supplement the work we are doing but not anything that seeks to replace the actual journalistic standard that our folks can apply. I don’t want a bunch of bots out there throwing together information about what happened at the City Council meeting.”

Bernier knows not everyone in the newsroom is going to adopt these technologies right now. Reporters, in particular, are skeptical by nature and value the process of uncovering information on their own to share the truth. Plus, who has the time?

“Our top priority is getting the news out, and unless we shut down the station for a week to learn this new tool, I think people have to find a way on their own time,” he said. “I think for most people, that’s a big ask because their plates are full. This just happens to be something I am personally interested in as a tech nerd.”

As Bernier talks, he points out all the screens in his home office — 10 total if you count his iPhone — along with scanners, synthesizers, amps and electric guitars.

“I am into AI,” he said. “Someone else might be into nonfiction books to inform them about their beat.”

In addition to writing code, Bernier has thought of even more basic uses for ChatGPT that any reporter could adopt. He highly recommends using it before interviews to think of relevant questions to ask sources.

He asks it: “If I were going to report a story about the dangers of low water crossings, what kinds of things would I want to know?”

"There are so many uses out there that we haven’t even thought of yet,” Bernier said. “We can’t ignore AI because it is going to completely revolutionize the news industry, and we want to use it for good."

Have we already gotten away from that? Will robots soon take over the world?

Maybe not, Bernier said: “It’s something I think about every day.”